I’ve been experimenting recently with the open source music notation software LilyPond (thanks CDM!). I had looked into it in 2005 or 2006 and couldn’t understand how it would be of much use to me at the time. I think I recognized the flexibility of LilyPond, but couldn’t justify learning a scripting language (programming language?) when Finale met most of my notation needs. Since then I’ve become increasingly frustrated with Finale–more reluctant than ever to shell out more money for another incremental upgrade that never seems to provide the features I need. At the same time I’ve become more interested in creating non-standard notation, and so I developed a workflow in which only bare bones musical notation was produced using Finale, with the rest of the layout work done in a graphic design program like Illustrator. I’ve also been working more with tablature for five-string banjo, which has never felt comfortable in Finale.

So when I came across LilyPond this time I immediately noticed the support for non-standard notation, everything from Gregorian chant notation to proportional notation found in contemporary music, and of course, tablature. I also saw examples of common (for me) notation tweaks and features such as staves without bar lines; staves in multiple, simultaneous time signatures (that align!); note heads without stems; staves without staff lines (blank staves); note clusters; quarter tones; various accidental-handling schemes, etc. More encouraging was the fact that these features, while not always highlighted, also weren’t buried in the back of the documentation and were presented as viable (even desirable) notational choices. And did I mention that the output looks amazing! LilyPond produces gorgeous scores.

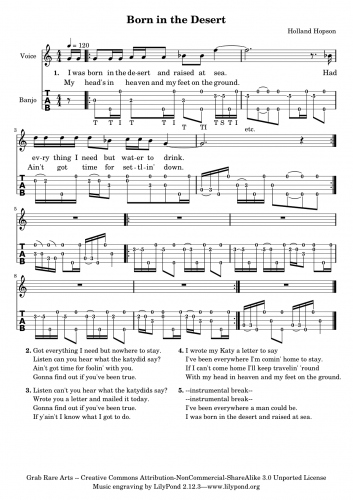

With those encouraging signs I jumped right into the tutorial and quickly decided I would try to notate some of my songs for five-string banjo. After about about a week of daily half-hour sessions I had a usable score for “Born in the Desert” and a new found enthusiasm for LilyPond.

Download the score as a pdf file: born_in_the_desert.pdf

Download the score as a LilyPond .ly file: born_in_the_desert.ly

Working with LilyPond

LilyPond uses a scripting language for all input: there’s no GUI, no point-and-click, no pretty graphics. I suspect my initial reluctance to try LilyPond the first time around was largely a result of this structure. (“What? I have to type out a bunch of ASCII? And then compile it to see the result?”) After a short time with the language, however, I found I quite enjoyed working without a GUI. Here are a few reasons why:

WYSIWYM: LilyPond operates on a “What You See Is What You Mean” principle. I like the fact that I can encode the information that’s important to me separately from its presentation. Working with tablature provides a good example. In some tablature programs, your data only “looks” like actual notation. Behind the scenes it’s actually a collection of graphics commands and specifications–a drawing that resembles music. If you decide later to extract the notation, or even simply transpose it or try an alternate tuning, you quickly find you’re stuck; there’s no (musically significant) “there” there. In LilyPond, you encode the important data and then decide how to present it. If you later change your mind about the presentation, the original data is still around, preserved in a musically sensible manner.

Variables: I may be more of a programmer than I realize or admit to being, since I immediately grabbed on to the powerful options presented by variables. Anything that can be represented in LilyPond can be assigned to a variable: from a recurring rhythmic motive, to a sequence of pitches, to an entire staff of notation. This provides composers with the ability to generate a personal “language” of modules.

I used two simple variables in the score for “Born in the Desert”. One holds a recurring “pinch” gesture that will be familiar to fingerpicking guitar and banjo players. I named it “pinch”

pinch =

{

< g’\5 d’ >8

}

This simply creates an eighth-note chord consisting of a d and g above middle c. The “\5” after the g tells LilyPond that this note belongs on the fifth string.

The other variable contains a similar sequence of notes, a sixteenth-note g on the fifth string played by the thumb followed by a d on the first string plucked by the index finger. I named this variable “ti” for thumb-index.

ti = {

g’16\5 d’

}

My use of these variables is far from earth-shattering but felt wonderfully convenient. Every time I needed to represent these gestures all I had to do was type \pinch or \ti.

Note to self: I enjoyed how useful writing comments to myself could be. If something wasn’t working exactly how I wanted it I could simply add a comment like “% ??? what’s going on here? why is the second verse not aligning the way I expect?” or “% FIX This bar may need to be transposed.” These kinds of placeholders are nothing special in a word-processing environment, but when working with a graphical notation tool I often resorted to maintaining a separate “to do” file that was clumsy to use since it required including wayfinders like: “violin part, page 6, bar 23, beat 1: …”

And here are a few frustrations with Lilypond, all having to do with its script-based nature:

“error: failed…”: Seemingly trivial lapses in syntax can produce disastrous results. More than once I forgot a curly-brace or a quote and witnessed a dismaying string of errors pop up in the console when I tried to compile the score. A little bit of code management and common sense goes a long way here, such as indenting blocks of code and adding plenty of comments. I also found working with LilyPond within jEdit provided excellent color-coding of syntax.

Move it!: Sometimes I wanted to nudge a notational element or move staves a bit closer together. With Finale or Sibelius there is often a simple click-and-drag solution. in LilyPond I was back to poring over the documentation to find the correct \override statement and which engraver to invoke. Sound tricky? It is. And for simple fixes it was frustrating (though I’m sure with time the simple \overrides would become second nature). The one consolation is that the same \override principles are used to move practically _anything_ in LilyPond, providing a degree of flexibility that Finale or Sibelius simply don’t offer.

LilyPond Life

My next step with LilyPond will be producing scores for more banjo tunes to be released in conjunction with my upcoming CD. I’m particularly interested to find out how flexible the tuning schemes for tablature can be. LilyPond’s banjo tablature supports a number of common tunings already. I wonder how will it handle the non-standard tunings in some of my pieces. Then I hope to tackle some of the more outlandish notational problems in my existing works that have previously prevented me from rendering them electronically.